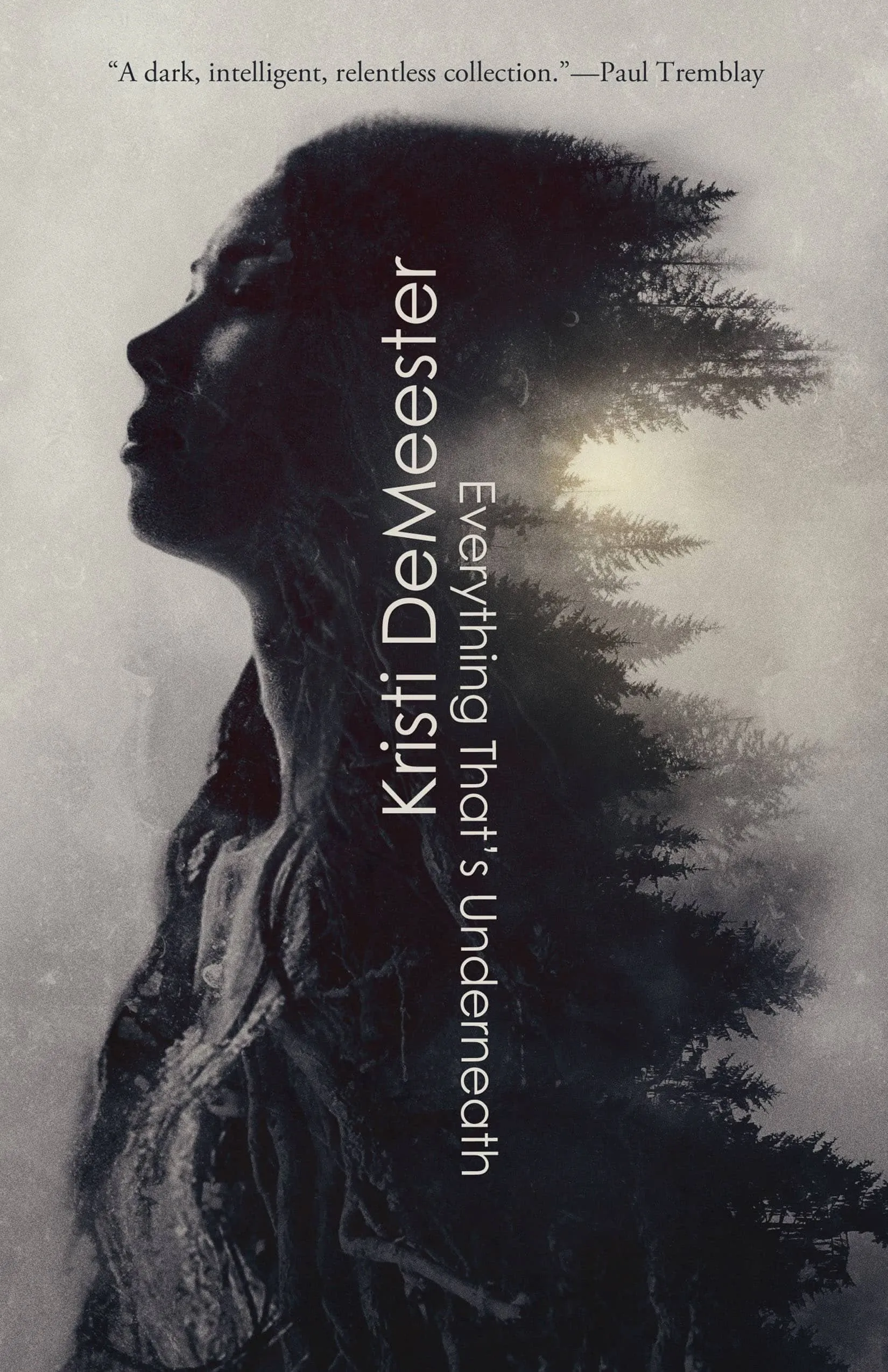

In Kristi DeMeester's transformative dark fantasy collection, Everything That’s Underneath, the author explores the places most people avoid. A hole in an abandoned lot, an illness twisting your loved one into someone you don’t recognize, lust that pushes you further and further until no one can hear your cry for help. In these 18 stories, the characters cannot escape the evil that is haunting them. They must make a choice: accept it and become part of what terrifies them the most or allow it to consume them and live in fear forever.

Crawl across the earth and dig in the dirt. Feel it. Tearing at your nails, gritty between your teeth, filling your nostrils. Consume it until it has consumed you. For there you will find the voices that have called from the shadows, the ones that promise to cherish you only to rip your body to shreds.

Table of Contents

Everything That’s Underneath

The Wicked Shall Come Upon Him

To Sleep Long, To Sleep Deep

The Fleshtival

The Beautiful Nature of Venom

Like Feather, Like Bone Worship

Only What She Bleeds (short story original to collection)

The Tying of Tongues

The Marking

The Long Road

The Lightning Bird

The Dream Eater

Daughters of Hecate

Birthright (novelette original to collection)

All That Is Refracted, Broken

December Skin

Split Tongues

To Sleep in the Dust of the Earth

Excerpt

Gable began turning into a bird at night two days after her mother died.

“Gable is a boy’s name,” one of the grandmothers said and turned her teacup in gnarled hands. A dark wart hung from her left eye, and Gable thought of snatching it between her fingers and dropping it into the tea that the group of old women, who had come to visit and help her mourn, requested that she make.

Gable had not wanted to make the tea, the itiye the old woman expected, and when she heard their slow footsteps on the front porch, she had thought of running, her legs tearing through the thick bamboo that grew up to the back door of the small bungalow she had shared with her mother for seventeen years. In the end, she had not and opened the door to their wrinkled faces that twisted into concern and sorrow when they saw her.

“Uma named me,” Gable told them, and they clicked their tongues and shifted large bottoms against too small chairs.

It wasn’t entirely true. Gable was her nickname. After her mother’s favorite film star. Over and over they had watched the movie. Scarlett with her tiny waist and voluminous skirts, and Rhett with a smile that Uma said the devil had sneaked inside of. A handsome smile. In this tiny Florida town far from their home of South Africa, it made Gable proud that she carried his name.

When she was born, Uma had gifted her a traditional Xhosa name. Lindelwa. The awaited. After the Inkaba, after the burning of the placenta and the umbilical cord, her mother had whispered her true name into the smoke, and had only called her Gable. She did not know how to be anyone else.

“It is a disgrace,” another grandmother said.

“You’re one to talk. Hair like a white woman,” wart face said, and the other woman patted her platinum blonde hair that she had cropped short against her skull.

“I am an old woman. I can do as I please.”

Gable turned from them and carried the pot back into the kitchen, but she could still hear their muffled voices worrying for her. Pitying her.

From the sitting room, a single word floated to her, and she brought a fist against her stomach thinking that it would keep her from unraveling.

“Amagqhira.”

They would expect her to take her mother’s place.

When the first dream had come to Gable, she was seven, and her mother held her tight when she awoke screaming into the dark. Uma did not scold Gable when she vomited over her mother’s dress and the bed sheets, but smoothed her hands over Gable’s face, and whispered to her. “It is like drinking the stars. Hard and sharp inside of your belly, and they burn and burn. You cannot keep them. The dreams. They must come out. No matter how good. No matter how bad.”

No one had ever expected Gable to meet a man. No one would marry a girl so skinny that even the smallest dresses had to be taken in, and a face that was so dark, so plain. A face filled with darker eyes that seemed too large.

She would never be a mother.

“Your life will be the drums. The chanting and the music and the dreams. Bones in the dirt, and the people will come to you,” her mother had told her that night, and Gable had swallowed the idea down, tucked it deep inside of herself like a beautiful jewel that only she and Uma had known about.

Now, standing inside of the tiny kitchen that Uma had kept scrubbed clean, Gable could not think of herself sleeping alone in this house. Day in and day out the people tramping dirt into the carpets and asking her for guidance from their ancestors over the stupidest of things.

Without Uma, the life that she had seen for herself since she was a girl rose up and choked her, dragged her down like a chain attached to her neck.

Setting the teapot on the burner, she waited for the water to heat. The grandmothers had not asked for more tea, but she needed to be away from them, away from their probing eyes and thinly disguised questions.

Again, their voices rose in the next room, and one of them laughed, a sly, high-pitched tittering that implied someone had told a dirty story. Probably about one of their husbands and how he couldn’t get his pecker up.

Gable had heard variations of the same stories from the same group of women hundreds of times, and she had always been thankful that she would never be one of their kind. A used up woman with nothing better to talk about than her husband’s shriveling penis.

The water boiled, and she dropped in the leaves and tried to ignore their snickering. She wished they would go away, leave her to the quiet of the house. She wanted nothing more than to sit in Uma’s bedroom, lie down on her bed, the smell of smoke and incense thick in the room, and wait for the dreams that would surely come. The dreams Uma had promised her.

“Lindelwa? Our tea has grown cold.”

Now that her mother was gone, she would never be Gable again. The grandmothers, the people of her little town would call her by her birth name, and eventually, they would call her something else.

Amagqhira. The healer. The diviner.

Gable went back to them and refreshed their tea. They sat with her until the first streaks of night slipped into the room, and then they each stood and patted her shoulders and cheeks as they made their way to the door.

“Goodnight, Umamkhulu,” she said, and then she shut the door, listened as they shuffled away. She counted to two hundred, then five hundred to be certain that they had actually gone, that one of them had not decided to turn back, determined to stay with Gable through the night.

Had that happened, Gable would have run. Straight out the back door and into the dark stalks of bamboo that stretched green fingers into the night sky. Ran until the feathers began to sprout and her bones shifted to make room for something lighter.

Even now she did not know how much time she had left. Each night had been different. The first night she had woken halfway through the transformation and had been so frightened that she had hopped into the closet and stayed there until morning.

She had slept, remembered dozing off, but she had not dreamed, and in the morning, her legs were her own legs, and she had drank glass after glass of water, but she was still thirsty.

She’d spent the day wandering through the house, arranging and re-arranging the picture frames, the small wooden figurines of birds that her mother had loved so much, but her skin would not rest easy on her bones. For hours, she walked down the streets of the country she had come to know as her own. The country that her mother and so many of their people had adopted, but she could not settle into the cracks in the asphalt under her feet and came back to the house with its blue clapboard siding and white shutters and waited for night to fall.

Tonight, she threw open the back door and walked into the bamboo. As she went, she unbuttoned the simple green shift she’d put on that morning, her shoes left beside the door, and walked into the darkness, traced her fingers over the dew that clung to her skin.

And she waited.

§

“The Lightning Bird comes in the night. Only in the night. Flying on the wind, carrying the witch’s words inside of its eyes, and it sees for her. Hears for her. If it finds you, it will open you up. Mamfu! Chomp, chomp! Take your blood until it has its fill and then leave you lying there. Your skin rattling around your bones.”

The older girl leaned over Gable, her eyes wide. “That isn’t true. Uma told me,” Gable said, and the girl threw her head back and laughed.

“Do you believe everything your Uma tells you, little girl?”

The older girl’s name was Sisipho, but everyone called her Sisi. On nights when her mother went visiting, Sisi stayed with her. To make sure that Gable didn’t get into any trouble, her mother said, but Gable never got into trouble, and she hated this girl who was only two years older than her fifteen years. Hated her for her soft hair and light amber eyes that crinkled in the corners when she smiled. Hated her for the way every boy, every man, would turn his eyes toward her swaying hips as she walked, her breasts straining against the thin dresses she wore.

“No, of course not. And I’m not a little girl,” Gable told her, but of course she believed her mother. Uma knew things. Her dreams told her. The bones she threw told her. And Uma would not lie to her only daughter.

Uma had told her about the Lightning Bird, Impundulu, but it was not the fearsome creature that Sisi described. Her mother’s eyes had gone soft and dreamy as she talked of a beautiful black and white bird that could be small enough to fit in the palm of your hand or big enough to fill the entire sky.

“Impundulu brings lightning. The rain. Gives us eyes in the night, lets us see the entire world opened up. A familiar. Impundulu has visited me, has served as my eyes. One day, it will visit you.” her mother said and smiled a slow, heavy smile.

“Watch for him, Gable. You may wake to him in the night, a beautiful man at the end of your bed, and he will take down the bed sheet, and lift up your dress.” Sisi pinched at the tops of her thighs, and Gable slapped her hands away.

Gable left Sisi roaring in the kitchen and made her way outside. More and more frequently, her mother visited on the old grandmothers, held their hands and guided them from this world to the next. So many of them nearing the end of their time, and they called for Uma day in and day out, and Gable tidied the house while Sisi watched, made herself a meal that she did not eat, and then wandered through the bamboo until the moon rose.

Her mother had not talked about the black blood that Gable had found in the toilet. Uma had not had her monthly blood in a long while, and Gable was far from her own cycle. When she asked about it, her mother pressed her lips together and went back to her herbs.

“It’s nothing, Gable,” she said, and Gable had not asked again. She knew better than to press her mother to reveal something that she did not want to.

Gable had her own secrets. The darker visions that came to her, the ones that left her heaving with hot tears slipping into her mouth that she gobbled down. Fathers sweating and heaving over their daughters like beasts while mothers cowered in the next room, their hands clamped to their ears and a curse that would never come true on their lips. A son eating his meager breakfast and thinking of putting a pillow over the face of his mother, holding her there until her clawing hands fell slack, those terrible hands that would never rise to strike him again. She would not reveal them to Uma. Could not.

Uma’s visions were of joyful things. Marriages. Births. Fortune. Her daughter’s visions came with the darker tinge of nightmare, and when they came, Gable locked them inside and pretended that she had eaten something spoiled, that she needed to use the toilet. Nothing more.

“Some of us see the shadow world. Dream of terrible, terrible things. But we are still the amigqhira. We do our jobs,” her mother had told her once, standing in front of a large, boiling pot of soup, and Gable had cast her eyes downward even as her mother watched her carefully. If Uma knew, she never spoke of it to Gable.

Now, standing amid the bamboo, she closed her eyes, and thought of the drums, hard and heavy in her ears, her voice lifted to follow them, and her feet rose to match their rhythm. Her voice lifting into the old chants, the ones that would carry her spirit far from her body. The ones her mother had forbade her to use.

Out of the bamboo, above the house, she floated, followed the scent of her mother. Incense and oranges on her tongue as she followed her mother into a dark house, the sharp tang of citrus overtaken by the cloying smell of rotting flesh. Disease buried deep and working its way outward.

But it was not the older woman who smelled this way. Death had marked her. That was certain. Even Gable could see it from her place in the doorway, but the disease was in her brain, not in her body, and the decay that Gable smelled now came from her mother.

Uma turned and fixed her eyes on the spot that Gable occupied, and Gable fled the doorway, made her way back to her own body where she lay sweat slick under the green canopy waiting for Sisi to burst through the back door and tell her to come back inside.

When the girl finally did, Gable rose and made her way back to the house, gathering her dress against her as she went to ward off the chill settling deep into her flesh.

Her mother came in late. Gable heard her opening the door, taking off her shoes, before moving to the kitchen, and starting the burner for tea.

The door banged again as Sisi left, no doubt tucking the bills Uma paid her inside the small woven bag that she carried.

Gable pretended to sleep when Uma drifted past the door, but her mother did not pause to look in at her as she had on so many other nights. Instead, she went on to her own bedroom and closed and locked the door behind her.

In the morning, they did not speak, and Gable sat at her mother’s table and fought to keep from crying.

When her mother slipped a small black and white feather into the itiye she poured, Gable pretended not to notice and drank it down.

§

Gable visited the houses of the old grandmothers. Feathered and sleek inside of her new skin, she pulled fat grubs from the earth and dropped their wriggling bodies into the women’s hair. She plucked spiders from airy webs and placed them on their slack, snoring mouths, delighting when one spider managed to crawl inside.

It was stupid and juvenile, and she should be ashamed, but she could not stop herself and flitted from house to house delivering her small gifts. These women with their barbed, gossiping tongues. They deserved something nasty.

The night air pulled at her, hard and insistent. The stillness in those enclosed houses and rooms stifled her, and she moved more and more quickly. If anyone were to wake, they would see only a bird, a blur of black and white feathers as it sought an exit, and then tumble back into dreams and forget.

Eventually, she found herself perched at the foot of a bed, staring down at the sleeping form of a young woman. Her belly swelled with child, and she twitched in her sleep, her hands pressed against the life that sparked there.

Gable did not remember flying here, to this house, and her mind searched back and back, but everything was dark.

Sisipho lay before her, and the girl reached out a hand to the opposite side of the bed. When she found it cold, found it empty, she withdrew her hand and frowned in her sleep.

Watching her, Gable felt no pity. Sisi had chosen poorly. A stupid, infatuated girl whose mother had to rush the marriage ceremony so that no one would see the slight bulge already appearing under her daughter’s dress.

Gable crept closer and pressed her beak against the hot skin stretched tight. It would be nothing, nothing at all, for her to push against that membrane, let the blood rush into her mouth, hot and bitter, and drink until she was full.

“Impundulu,” the voice said, and Gable looked up into Sisi’s open eyes. Her face was wet.

“Please,” Sisi said. “Take it out. Take it out of me.”

Gable traced her beak down Sisi’s abdomen, let it come to rest at the crest between her thighs, and breathed in. Salt and blood and sweat, and Gable was so thirsty. It would be so easy. So simple to take what she wanted.

From Sisi’s inner thigh, Gable tore away a chunk of flesh and gobbled it down where it sank like a stone inside of her. She could not bring herself to take more, no matter how it eased the burning in her throat.

She left the girl she had once known lying beneath her and sobbing, her hands twisted around bedclothes gone dark with blood.

Until morning she flew without stopping and without awareness. There was still the taste of blood on her tongue like burning iron, and it was only when the sun finally rose that she slept and did not dream.

§

When Gable turned sixteen, her mother stopped going out. Shut away in her bedroom, Uma spoke in low tones, instructed her daughter on how to take her place. From house to house, Gable fell into her mother’s patterns, and the people came to smile when they saw her, and eventually, they did not ask after her mother, did not wonder when she would return.

Under moonlight and weak flame, Gable washed her mother’s wasting body, gathered old blood in a wooden bucket and carried it into the bamboo, dumped it back into the earth. There kneeling under the sky, she would let herself drift into the darkness, her lips barely moving as she chanted, the tiny skull and vertebrae of a bird pressed into her right hand as she threw them into the dust.

“Save her,” she whispered, but the ancestors did not hear, and every day her mother withered.

“I cannot do this,” she said two nights before the last breath her mother drew. “Not without you.” She could not tell her mother that she was frightened. Could not tell her of the nightmare she’d had the night before. Blood like a river flowing over their bodies. The both of them, submerged. Drowning. And the terrible bird, rising from the waters, its white feathers stained crimson.

Uma lifted her eyes, fever bright and rolling in their sockets. “Intombi. My little daughter. My little bird. Give me your hand.”

Rising up onto her arms, her mother panted. “Not alone. Dream of me, intombi. Dream of me and bring me back,” she said, and then her eyes fluttered backward, and she fell onto the pillow. She did not speak again, and in a day, her breathing slowed.

The old grandmothers found the two of them together, had to pull Gable away from the body, and still, she screamed and clung to the cold fingers.

“Leave us!” she told them, but they clucked their tongues and shushed her, smoothed her hair back as they whispered that it was better this way.

Gable let them bend and shape her body as they wished. Watched as their people streamed into Uma’s home, watched them slit the throat of a goat that should have been oxen, and opened her mouth to receive the small portion of meat that was meant for her and her only.

The women had not left her alone that night, and she closed the door of her bedroom on their small sounds. Again and again Gable chanted, tried to catch at the sounds of drums, but sleep would not come, and her mother’s body lay in the next room, a cold, rotted thing that would not rise again.

§

In the morning, Gable’s mouth was foul with the taste of Sisi’s skin. Twice she had vomited, but still, she could feel Sisi inside of her like a dark, wet seed taken root.

Outside, the sky turned black. Clouds piled one atop another, and she went to the kitchen and turned on the light. The faint yellow glow did little to chase away the gloom, so she turned to the window to watch the storm.

When the thunder began, her stomach clenched around the hollow Sisi had left, and she heaved. A thin line of drool fell from between her lips, and she sank to her knees, her fingers splayed before her, as the floor seemed to drop away and the back door blew open.

Again, her stomach contracted, and she gagged until a dark feather fell from her lips.

Taking it up, she smiled into the storm creeping into the kitchen. Lightning cracked in the distance, and the room flooded with ghostly light. The thunder drummed against the house, and she stood and gave herself over to the sound.

The heady scents of orange and incense flooded the small room, and she breathed them deep, took her mother’s smell inside of herself and hid it away.

“Uma,” she spoke into the lightning, and it was as if the lightning itself answered. The sound broke her wide open, and she sank to her knees under her dead mother’s voice.

“Bring me back, Gable. Lindelwa. Little daughter with your dark dreams. Bring me back.”

She thought the light would tear her apart, and she closed her eyes against it, but it still wormed along her skin, cutting against her with tiny, hot teeth, and she clawed at her dress, ripped at her hair. Everything burned and burned, but it was not beautiful in the way that she had always thought lightning to be.

Ugly and painful and ugly, and she could not escape, but there was her mother’s voice, and she gave in to it. Sank into it like hot water, and her mother kissed her face and her hands, and Gable let her mother wipe the tears from her cheeks and the blood from her mouth, and there was no reason to fear.

Uma had died, had crossed into the place of ancestors, but she was here, with Gable, and it didn’t matter how it had happened, didn’t matter that it made no sense.

Cradled and safe, she followed her mother down into the dark, the places where Gable’s dreams dwelled, and her mother fed Gable from her own mouth, and she ate hungrily. She drifted and dreamed, images of water and feathers and shadowed places opening their mouths, and the thunder coursed through her, the lightning burning inside of her veins, and she was again inside of the river of blood, but this time she did not drown.

“Bring me back, Gable,” her mother said again, and the thunder stopped, and she lay on the kitchen floor, her dress torn to shreds, and her monthly blood between her legs.

Rising, she went to the sink, ran the water until it went hot, and then passed a rag beneath it. Carefully, she cleaned herself, and the water turned pink with her blood. When her skin was clean, she pulled her torn dress over her head and walked through the house naked. Here and there, she touched her fingers to a figurine, to a ceramic bowl, hard and smooth under her fingers, to the delicate lace embroidered along the bottom of the white curtains.

When she came to her mother’s bedroom, she opened the door and moved to the old dresser, pulled a dress from the drawers, and tugged it over her head. It did not fit, but it did not matter.

With her mother’s dress against her skin, she lay down on the bed, felt her blood come hot and thick between her thighs, and waited once more for nightfall.

§

When Gable came to Sisi’s house, all of the windows were left open. Heavy curtains hung listless against glass, and she pushed herself through, the sash grazing her back.

The house was cold, and the rooms smelled of stale air and the slight salty tang of unwashed bodies. Gable stretched her wings to their full length, allowed herself to fill the room. She did not have to hide, did not have to tuck herself away into small corners, a tiny, skittish thing that moved on the night wind.

The rooms were dark, and Gable made her way through the sitting area crowded with piles of clothes that stank and down the hallway where a lone door stood open. From inside came the small sounds of someone pretending to sleep.

Sisi sat up when Gable pushed herself through the door, the lower half of Sisi’s face cloaked in shadow as if the dark was slowly gobbling her up. “Who do you work for, Impundulu?”

Gable did not need to answer her question. Uma’s spirit burned through her like lightning, shook her heart like thunder. There had never been anyone else. Just the two of them moving through the shadow world, their dreams thick on their tongues, the hard angles of bones clutched against their palms, and the taste of incense lingering in their mouths. Mother and daughter together as one.

Gable went to the girl then, and Sisi lay back, went quiet while Gable, while the Lightning Bird, moved above her, the bloodied beak dipping in and out of that secret place that created life. A life that had not been wanted but now rushed inside of Gable like strong, clean water. The current of a river filling her up until she thought that she would stop breathing.

In the morning, Sisipho’s husband would stumble home, his hands stinking of another woman’s body, and all that he would find was the empty shell of the woman he’d been forced to marry.

The old women would gather and mourn Sisipho, mourn the loss of her child, and Gable herself would perform the umkhapho, blood running over her hands as she ensured the first step in Sisipho’s descent into the world of ancestors.

Eventually, Sisi would appear before Gable in a dream, as the death ritual indicated, her teeth stained red, and Sisi would whisper that she was hungry. So hungry. And Gable would do what was expected of her—the amagqhira, the diviner, the healer—and guide her through.

§

The grandmothers brought Gable gifts. A small cradle. A soft blanket knitted with patient hands. Several pairs of leather booties. A beautiful sling dyed the color of the sky at twilight. They left these at her doorstep and went away quietly. In the silence of their own homes, they did not speak of Gable, did not speak her swollen belly or her careful smile.

Alone in her mother’s house, Gable waited. When the baby kicked, she sang to it, all of the songs that Uma had taught her, and from deep inside, the child remembered who it had once been. Gable was sure of it.

When the time came, the contractions shuddering through her, she bit down on her screams and walked deep into the bamboo. Panting, she squatted over the earth and let the pain roll over her, lost herself inside of a darkness so deep that she wasn’t sure she would ever break the surface, but then there was only a deep ache inside of her and the world filling up and everything stretching and tearing and there was only this moment, this bearing down, and the sky opening above her with brilliant light, and her blood rushing through her like thunder.

The girl child did not cry when her mother cradled her against her breast. Gable wiped the blood from the baby’s face and brought her lips to the small, sweet forehead, breathed in the smell of citrus and beneath that, a smell of something much older.

Gable’s daughter looked up with eyes the color of a deep river.

Eyes the color of dark feathers.

About the Author

Kristi DeMeester is the author of Beneath, a novel published by Word Horde. Her short fiction has been reprinted or appeared in Ellen Datlow's The Best Horror of the Year Volume 9, Year’s Best Weird Fiction Volumes 1 and 3, in addition to publications such as Black Static, Apex Magazine, and several others. In her spare time, she alternates between telling people how to pronounce her last name and how to spell her first. This is her first short fiction collection.

Cart(

Cart(